4n6ir.com

Block Hunting

by John Lukach

In DFIR practices, we use hash algorithms to identify and validate data of all types. The typical use is applying them against an entire file, and we get a value back that represents that file as a whole. We can then use those hash values to search for Indicators of Compromise (IOC) or even eliminate files that are known to be safe as indicated by collections such as National Software Reference Library (NSRL). In this post, however, I am going to apply these hashes in a different manner.

The complete file will be broken down into smaller chunks and hashed for identification. You will primarily have two types of blocks, a cluster and a sector. A cluster block will be tied to the operating system where sector blocks corresponds to the physical disk. For example Microsoft Windows by default has a cluster size of 4,096 that is made up of eight 512 sectors that is common across many operating systems. Sectors are the smallest area on the disk that can be used providing the most accuracy for block hunting.

Here are the block hunting techniques I will demonstrate:

- locate sectors holding identifiable data

- determine if a file has previously existed

I will walk you through the command line process, and then provide links to a super nice GUI. As an extra bonus, I will tell you about some pre-built sector block databases.

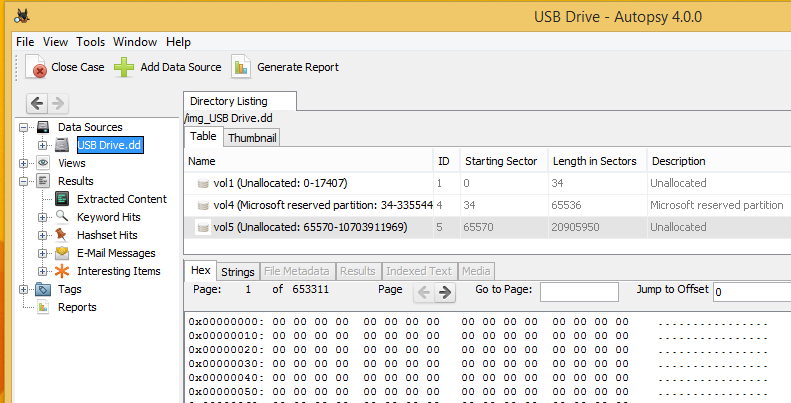

Empty Image or Not

If you haven’t already, at some point you will receive an image that appears to be nothing but zeroes. Who wants to scroll through terabytes of unallocated space looking for data? A quick way to triage the image is to use bulk_extractor to identify known artifacts such as internet history, network packets, carved files, keywords and much more. What happens if the artifacts are fragmented or unrecognizable?

This is where sector hashing with bulk_extractor in conjunction with hashdb comes in handy to quickly find identifiable data. A lot of great features are being added on a regular basis, so make sure you are always using the most current versions found at: http://digitalcorpora.org/downloads/hashdb/experimental/

Starting Command

The following command will be used for both block hunting techniques.

bulk_extractor -e hashdb -o Out -S hashdb_mode=import -S hashdb_import_repository_name=Unknown -S hashdb_block_size=512 -S hashdb_import_sector_size=512 USB.dd

- bulk_extractor - executed application

- -e hashdb - enables usage of the hashdb application

- -o Out - user defined output folder created by bulk_extractor

- -S hashdb_mode=import - generates the hashdb database

- -S hashdb_import_repository=Unknown - user defined hashdb repository name

- -S hashdb_block_size=512 - size of block data to read

- -S hahsdb_import_sector_size=512 - size of block hash to import

- USB.dd - disk image to process

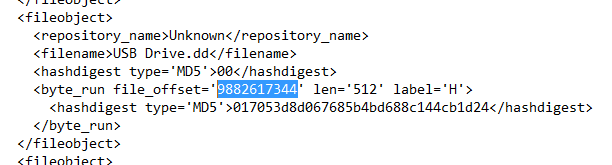

Inside the Out folder that was declared by the -o option, you will find a hashdb.hdb database folder that is generated. Running the next command will extract the collected hashes into dfxml format for review.

hashdb export hashdb.hdb out.dfxml

Identifying Non-Zero Sectors

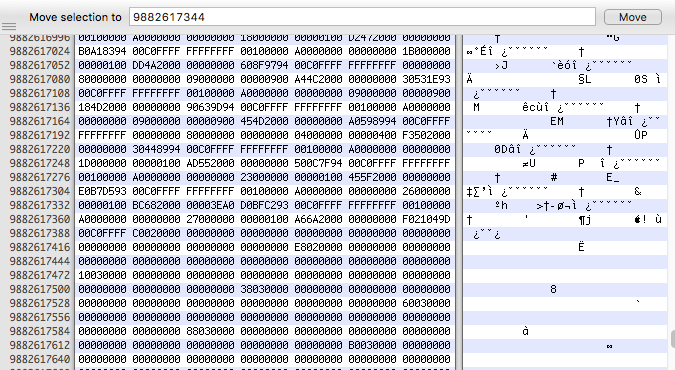

The dfxml output will provide the offset in the image where a non-low entropy sector block was identified. This is important to help limit to false positives where a low value block could appear across multiple good and evil files. Entropy is the measurement of randomness. An example of an low entropy block would be one containing all 0x00 or 0xFF data for the entire sector.

Here is what the dfxml file will contain for an identified block.

Use your favorite hex editor or forensic software to review the contents of the identified sectors for recognizable characteristics. Now we have identified that the drive image isn’t empty that didn’t require a large amount of manual effort. Just don’t tell my boss, and I won’t tell yours!

Deleted & Fragmented File Recovery

Occasionally, I receive a request to determine if a file has ever existed on a drive. This file could be intellectual property, customer list or a malicious executable. If the file is allocated, this can be done in short order. If the file doesn’t exist in the file system, it will be nearly impossible to find without a specialized technique. In order for this process to work, you must have a copy of the file that can be used to generate the sector hashdb database.

This command will generate a hashdb.hdb database of the BadFile.zip designated for recovery.

bulk_extractor -e hashdb -o BadFileOut -S hashdb_mode=import -S hashdb_import_repository_name=BadFile -S hashdb_block_size=512 -S hashdb_import_sector_size=512 BadFile.zip

The data will be used for scrubbing our drive of interest to run the comparisons. I am targeting a single file, but the command above can be applied to multiple files inside subfolders by using the -R option against a specific folder.

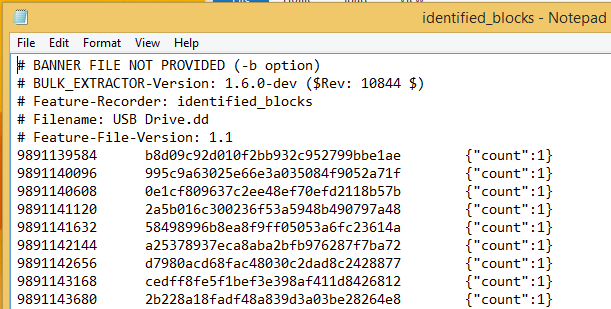

The technique will be able to identify blocks of a deleted file, as long as they haven’t been overwritten. It doesn’t even matter how fragmented the file was when it was allocated. In order to use the previously generated hashdb database to identify the file (or files) that we put into it, we need to switch the hashdb_mode from import to scan.

bulk_extractor -e hashdb -S hashdb_mode=scan -S hashdb_scan_path_or_socket=hashdb.hdb -S hashdb_block_size=512 -o USBOut USB.dd

Inside the USBOut output folder, there is a text file called identified_blocks.txt that records the matching hashes and image offset location. If the generated hashdb database contained multiple files, the count variable will tell you how many files contained a matching hash for each sector block hash.

Additional information can be obtained by using the expand_identified_blocks command option.

hashdb expand_identified_blocks hashdb.hdb identified_blocks.txt

Super Nice GUI

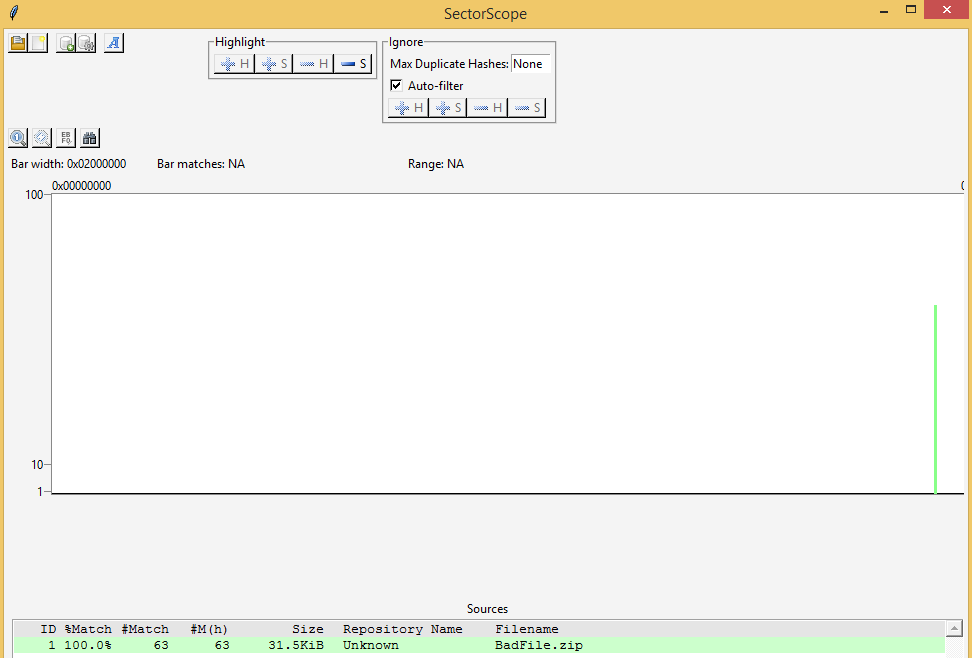

SectorScope is a Python 3 GUI interface for this same command line process that was presented at OSDFCon 2015 by Michael McCarrin and Bruce Allen. You definitely want to check it out: https://github.com/NPS-DEEP/NPS-SectorScope

Pre-Built Sector Block Databases

The last bit of this post are some goodies that would take you a long time to build on your own. I know, because I built one of these sets for you. The other set is provided by the same great folks at NIST that give us the NSRL hash databases. They went the extra step to provide us with a block hash list of every file contained in the NSRL that we have been using for years.

Subtracting the NSRL sector hashes from your hashdb will remove known blocks.

http://www.nsrl.nist.gov/ftp/MD5B512/

VirusShare.com collections is also available for evil sector block hunting too.

Happy Block Hunting!!

John Lukach

tags: Malware - OSINT