4n6ir.com

Fileless Application Whitelist Bypass and Powershell Obfuscation

by James Habben

Organizations are making the move to better security with application whitelisting. It is shown in the offensive side of the computer security industry. The frameworks, such as Metasploit, PowerSploit, BeEF and Empire, are making it very easy to build and deploy obfuscated payloads in all sorts of ways. It has become so easy that I am frequently seeing attackers using these techniques on systems that do not employ the added security measures.

There are plenty of solutions to mitigate these types of attacks, however I find they are not always configured properly. Take a read through @subTee’s Twitter feed and GitHub for many of the more creative ways he has shared. The attackers have raised the bar with the use of these techniques. If defenders aren’t deploying appropriate defenses, shame on them.

It Works

I wanted to share with you a few things from a recent engagement. The attacker had installed the backdoor almost a year before detection. They got in through a phishing attack, as in most cases. The detection? A kind and friendly letter from a law enforcement agency that had taken control of the command and control (C2) and was observing traffic to identify victims. The beaconing was surprisingly frequent for as careful as the attacker was in some other areas.

Can you confidently say that your endpoints are safe from these types of attacks? You don’t have to deploy prevention or detection tools for every part of the kill-chain, but you would be best served to have at least one. Or not, YOLO.

Persistence

In order for any malware to be effective, it has to run. I know, it is a revolutionary statement. It is a concept that is missed by some and it is a very critical piece. There are a finite number of places that provide malware the ability to get started after a system has been rebooted. Keep in mind that the user login process is a perfectly acceptable trigger mechanism as well, and there are a finite number of places related there too.

Just like the various creative and new application whitelist bypass techniques, there are creative and new persistence mechanisms found periodically. Adam has posted quite a few of them on his blog. The good news is that the majority of attacks don’t get that creative because they don’t have to.

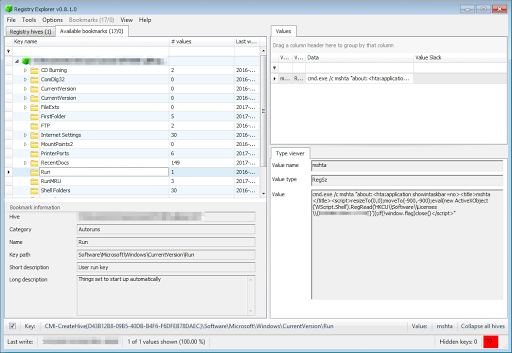

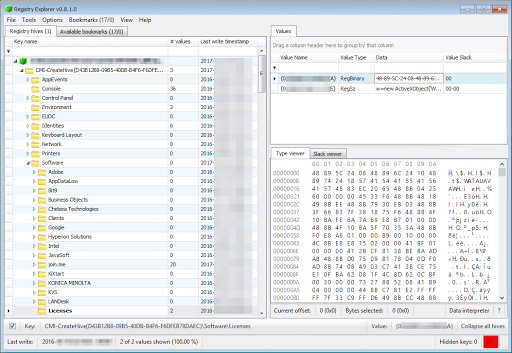

The run mechanism in this system was HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run

You can see that the attacker has chosen to use cmd to start mshta. The code following that command is javascript that when run creates an ActiveX object that loads more code from a registry path. So many layers!

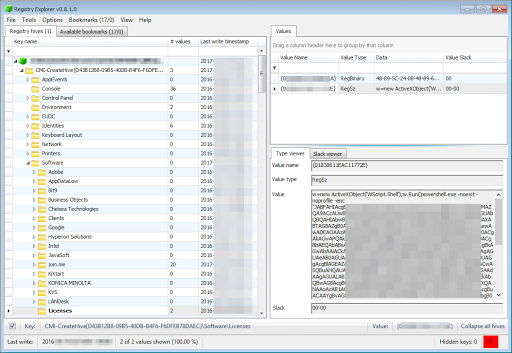

Obfuscation

The run mechanism loads in code that has been obfuscated by the attacker. It starts off creating another ActiveX object and then using powershell.exe to interpret the code following. The obfuscation is enough to prevent keyword searches from hitting on some of the known API function involved with these attacks, but it is not a difficult one to break. All you need is a base64 decoder. I recommend that you use a local application based since you never know what kind of thing will be showing up and an online javascript based decoder is susceptible to getting attacked, whether intended by the attacker or not.

The path referenced in the run value and pictured below is HKCU\Software\Licenses. I have blurred some code and value names in an abundance of caution for potential unique identifiers.

Decoding

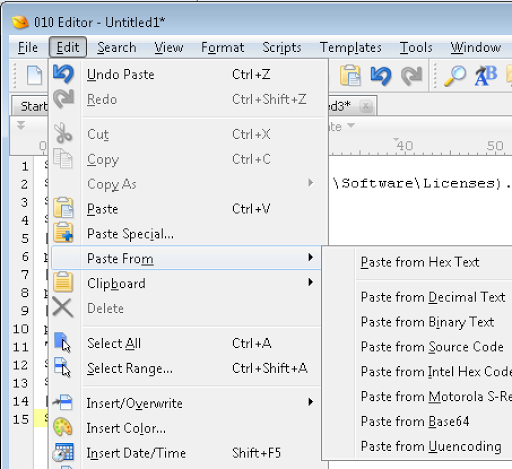

My preferred tool for decoding this is 010 Editor. It is not free, but it is worth its license cost for so many things.

First thing to do is copy the text inside those quote marks. Don’t include the quotes since that will throw off your base64 decoding.

Now you just create a new document in 010 and use edit > paste from > paste from base64.

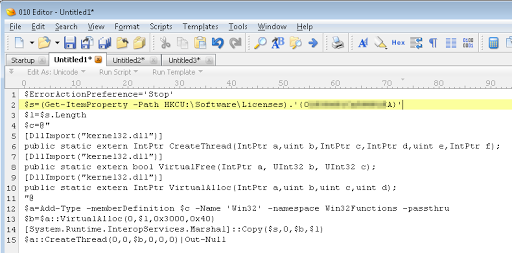

Magically you have some evil looking PowerShell code.

Take a look over at this powershell code from @mattifestation and you will hopefully notice that it follows the same flow. It looks like someone simplified the code from the blog post by removing the comments and shortening the names of the variables. Otherwise it is identical.

Payload

Line 2 of the PowerShell code loads the registry data from a different value in the same path. Line 14 then copies the binary data from the variable into the memory space for the process that was created, about 15kb of it. Line 15 then kicks it off, and the binary code takes over.

The binary is a shell code that decompresses a DLL image with aPLib and writes it into the same process space. The resulting DLL has not been identified by any public resources, so I can’t share it with you here. It is very similar to Powersniff and Veil, for those interested in the deeper analysis.

Raise Your Bar

Defenders, the bar has been raised by the attackers. Make sure that you are following suit, or better yet, raising it even higher.

James Habben

tags: Malware